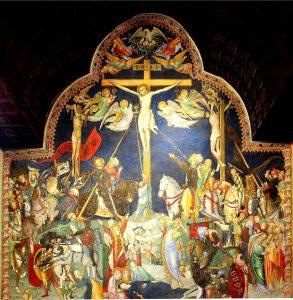

The Oratory of St. John of Urbino is always remembered, of the cycle of fifteenth-century frescoes (1416 c.) of the brothers Lorenzo (San Severino Marche, 1373 or 1374, † 1416-1420) and Jacopo (San Severino Marche 1347 circa – † after 1416) Salimbeni, the Baptism of Christ who, in fact, gives the “title” to the cycle itself. But of considerable interest and beauty it has always seemed to me the Crucifixion in which the style of the two mixes with truly unique results.

The two brothers in urbinate work, compared to that of St. Ginesius, adopt a technically more mature pictorial language, which is expressed in perspective solutions, chromatic finds and in presenting settings, scenes, costumes typical of the late Gothic era. The Crucifixion, on the back wall of the Oratory, is a composition that is largely unitary, but capable of highlighting and characterizing a sequence of events of human reality that go hand in hand with christ’s suffering on the Cross. Those who laugh decomposed, those who are engaged in a dialogue at least apparently foreign and disinterested in what is happening, are placed next to those who despair and weep for the tragedy in progress and mix with it, to present to those who are going to admire the whole thing, a drama that, if it finds its collation in the divine , feeds on a living and vegetated earthly reality, as if to remember that that time now past and far is still present and is renewed in everyday life. The taste for popular and lively narration, the meticulous observation of the details goes as far as almost moving away from the drama that is taking place. There are the painful and tragic expressionism of the twisted bodies of the two thieves hanging from the cross and now corpses, the weeping angels, the Magdalene and St. John torn apart by pain, the Maries who support our Lady unconscious, alongside episodes that reveal a daily attitude, almost facetious and loathing, as in soldiers who play dice , in dogs scratching, in courteous riders in the background, in the figure of the mother who subtracts the child by grabbing him by the arm from the paws of a horse and in the little boys arguing under the cross. It dominates next to a rarefied and courteous air typical of international Gothic, or late flowery, characteristic of the courts of Milan, Verona, Paris, Cologne, a more expressionistic and dramatic one with bright and contrasting colors typical of the environments of Bologna and Bohemia, which merge in their work and in general in contemporary painting of the Marche.

Probably it was of the two Lorenzo brothers who knew how to draw on a conspicuous artistic culture for the realization of these macabre subjects, starting from the scenes painted by Giovanni da Modena in the Cathedral of Bologna, or in the frescoes of the Camposanto of Pisa of the corpses painted by Buffalmacco, up to the macabre dances that filled the Cathedrals Of Europe , in particular the French ones, and made known by the circulation of miniatures. Of course, in the two brothers there is no lack of memory of Gentile da Fabriano, perhaps known right in San Severino Marche in the Duomo Vecchio where there are his frescoes, or perhaps met in Perugia. After all, marche was a region where international suggestions were facilitated by the established relationships that linked the local, albeit small, lordships with those of Veneto, Lombardy and Emilia, and where Marche artists could move and acculturate new international trends and flourish easily traveling between Bologna, Padua, Milan, Perugia and Florence.