Giovanni Santi doveva essere ben apprezzato alla corte urbinate e in tutto il territorio del Montefeltro e non solamente per le sue pale, ma anche per l’attività di ritrattista. Un genere che aveva evidentemente permesso al suo nome di varcare i confini del ducato di Urbino, visto che nel 1493 fu invitato da Isabella d’Este a Mantova per eseguire alcuni ritratti. Purtroppo non ci sono giunte sue opere di questo genere, ma credo che il figlio, già avviato all’arte dal padre, non possa avere fatto a meno di cimentasi, anche in giovane età, nella ritrattistica. Infatti sono due i ritratti disegnati fra i 16-17 anni da Raffaello (Knab 1983), e comunemente ritenuti degli autoritratti. Si tratta di due disegni, uno conservato al British Museum di Londra disegnato a gesso e l’altro conservato all’Ashmoleon Museum di Oxford a gesso grigio lumineggiato di biacca, che ritraggono un giovane che ricorda molto da vicino la fisionomia degli altri autoritratti di Raffaello, primo fra tutti quello degli Uffizi, con il dovuto passaggio del tempo e il relativo invecchiamento e entrambi segnati da una scritta pressoché identica di una mano tra il XVIII e il XIX secolo che recita: Ritratto di sé medesimo quando giovane.

Non c’è da stupirsi per il fatto che Raffaello si sia esercitato con la propria immagine, poiché era una prassi abbastanza comune per un giovane pittore e si pensi per esempio a Durer, al quale i due disegni sono stati a volte avvicinati (Knab).

1-2

Il disegno di Londra evidenzia uno sguardo diretto fisso nello specchio, ma non manca quella meraviglia tipica di un ragazzino di quell’età, anche se è percorso da un velo di tristezza o meglio di malinconia che, senza voler fare della psicologia, riflette forse lo stato d’animo di un giovane che proprio fortunato non era stato in quel primo periodo della vita, segnato da lutti famigliari, da eventi storici e politici che avevano sconvolto la patria, e da un rapporto con i parenti, specie quelli con i genitori della seconda madre, non certo edificanti. È comunque un ritratto molto realistico, che sembra quasi il primo o uno dei primi studi per una serie di autoritratti. In quello di Oxford vi è una idealizzazione più evidente e per questo vi si è visto un rapporto con i ritratti di Leonardo e Lorenzo di Credi (Beccherucci , 1968). Personalmente, anche per una questione di date, mi trovo più concorde con quegli studiosi che vi vedono un’influenza del Perugino e del Pinturicchio, senza dimenticare, anzi credo sia importantissima, la memoria di Raffaello della cultura Urbinate. Certamente Raffaello non aveva scordato i ritratti di Melozzo da Forlì, la scultura di Luca della Robbia e, soprattutto, non solo i ritratti del padre che purtroppo non ci sono giunti, ma i volti dipinti da questo, visi che sono trattati come dei ritratti (Zampetti ).

Il Serlio in un suo trattato afferma che Elisabetta Gonzaga, la duchessa di Urbino, era una delle protettrici di Raffaello, e questo ci fa dedurre che il giovane pittore fosse in relazione con tutta la corte, soprattutto per il fatto che l’attività culturale di questa era nelle mani della duchessa. Sembra quindi improbabile che la corte non abbia domandato al pittore di eseguire dei ritratti per i personaggi più in vista. È vero che i Montefeltro dovettero scappare davanti l’invasione e il tradimento del Valentino, ma dopo il loro rientro nel 1503, Raffaello avrebbe potuto eseguire dei ritratti. Effettivamente alcune testimonianze dell’esistenza di questi ritratti esistono, per esempio nel 1606 Antonio Beffa Negrini ci dice che esisteva un ritratto di bellissima e principissima signora, di mano di Raffaello Sanzio, che sarebbe appartenuto al Castiglione. Naturalmente è impossibile verificare se lo scrittore secentesco si riferiva al ritratto della duchessa di Urbino attribuito a Raffaello e oggi agli Uffizi, ma nulla ci vieta di pensarlo.

Non tutti sono concordi nell’attribuzione al pittore urbinate del ritratto di Elisabetta Gonzaga e molte sono state le proposte alternative, senza però giungere a delle prove conclusive. Ultimamente l’attribuzione a Raffaello si è fatta più forte da quando è stata accertata la provenienza urbinate del dipinto (Sangiorgi ).

3

Probabilmente Raffaello dipinse questo ritratto tra il 1503 e l’ottobre del 1504, prima della sua partenza per Firenze. È possibile, ma è solo un’ipotesi, che il ritratto sia stato eseguito prima della cerimonia di adozione di Francesco della Rovere da parte di Guidobaldo, che si svolse in Urbino con una grande festa e la partecipazione di illustri personaggi. Se Raffaello era in Urbino, come tutto fa credere, penso che pure lui abbia in qualche modo partecipato alle cerimonie. Allora il ritratto di Elisabetta potrebbe essere il primo di una serie per celebrare l’evento, che doveva comprendere tutte le più in vista personalità della corte, ritratti poi non eseguiti (o forse sì) per la partenza per Firenze.

E’ un ritratto frontale, anche se la duchessa ha la testa girata leggermente verso sinistra, movimento che rende alla perfezione il carattere aristocratico del personaggio. Veste un abito ancora quattrocentesco, sul collo del quale corre una scritta non identificata, probabilmente l’anima di un motto di origine ermetica, visto che alla corte di Urbino le ricerche ermetiche erano in gran voga, anche per il rinnovato clima neoplatonico che vi regnava. Sembra inoltre che proprio Elisabetta fosse una cultrice di tale cultura (Castelli). Non sarà facile decifrare questa scritta in caratteri cufici o simbolico ermetici e esoterici, anche se forse non sarebbe in un futuro errato consultare a tal fine il Corpus Hermeticum, che era già stato in parte tradotto dal Ficino fin dal 1471 con il titolo

L’acconciatura è anch’essa quattrocentesca, coi capelli che scendono lungo il viso e una scriminatura che li divide. Sono cinti in alto da una lenza che ha nel mezzo un piccolo e raffinatissimo gioiello, che rappresenta uno scorpione che racchiude nelle tenaglie una pietra preziosa. Si è molto discusso attorno a questo simbolo, che per alcuni rappresenterebbe il corpo del motto a cui si è già accennato (Baldi). In verità, anche per sciogliere questo enigma, si dovrebbe studiare a fondo la situazione, in quanto lo scorpione, fin dall’antichità, ha numerosi significati simbolici, alcuni dei quali contrastanti o di sapore squisitamente esoterico (Ceccarelli). Doveva essere, comunque, un simbolo molto caro alla duchessa, tanto che anche il Castiglione ce ne parla nel Cortegiano, quando la conversazione dei partecipanti si sposta proprio sul significato del gioiello, senza per altro fornire una soluzione.

Alle spalle della Duchessa si apre un panorama con prati e colli dietro ai quali sembra giungere l’alba. È dipinto con una particolarità che ricorda la pittura fiamminga, come d’altronde le fini pennellate da cui è composto.

Uno dei motivi che ha fatto dubitare sull’attribuzione a Raffaello di questo ritratto e di quello di Emilia Pio da Montefeltro, è la loro impostazione frontale un po’ arcaica, che contrasterebbe con i lavori del periodo fiorentino. Tuttavia, se la datazione è giusta, l’esperienza fiorentina era ancora da venire, oltre il fatto che alcuni critici spostano la data del lavoro di qualche anno in anticipo (Oberhumber ). Potrebbe anche essere che Raffaello, in qualsiasi momento abbia dipinto il ritratto, si sia ricordato di un altro quadro, molto probabilmente presente alla corte ducale in quel periodo, il Cristo benedicente oggi attribuito al Bramantino (Ciardi Duprè Dal Poggetto ). L’ipotesi può sembrare azzardata, ma mi sembra che vi siano alcune affinità tra i due dipinti. Non è tanto l’impostazione frontale a farmi sorgere questa idea, impostazione comune nel Quattrocento, basti pensare a Mantegna o a Antonello da Messina, quanto certi caratteri propri della figura. L’espressione ad esempio, in entrambi assorta, ma quasi distante con lo sguardo penetrante, il taglio degli occhi praticamente identico, come, d’altronde, il naso. Ripeto è solo un’ipotesi che dovrebbe però essere presa in considerazione.

4

Anche il ritratto a Emilia Pio da Montefeltro, del quale esistono testimonianze circa la provenienza urbinate (Sangiorgi), potrebbe essere dello stesso periodo e rientrare in quelli fatti per celebrare l’adozione di Francesco Maria. L’impostazione questa volta è del tutto frontale, non vi è nessun spostamento del viso. Lo sguardo, nobile e fermo, è fisso sullo spettatore, l’ovale del volto racchiuso da due bande di capelli che scendono sulle spalle. A differenza di quello di Elisabetta lo sfondo è scuro e tende a far emergere l’immagine.

5

Pure il Giovane con pomo, ritratto di sicura provenienza urbinate come attestano gli inventari e che finì a Firenze con l’eredità di Vittoria nel 1631 a Palazzo Pitti fino al 1928 per passare quindi agli Uffizi. Ritrarrebbe Francesco Maria della Rovere e dovrebbe essere stato dipinto in occasione della sua adozione da parte di Guidobaldo avvenuta a metà settembre del 1504.

6

Il personaggio, un giovane adolescente, veste riccamente abiti rossi decorati da una pelliccia e ha in testa un berretto con le falde rialzate sempre rosso. E’ rappresentato di tre quarti, con il busto verso sinistra e gli occhi a destra. Le mani appoggiano su di un piano e la sinistra è distesa sul palmo, mentre la destra stringe un pomo d’oro, il significato del quale non è del tutto svelato. Sono però incline a accettare l’ipotesi, già da altri avanzata, per cui il pomo sarebbe quello di Paride, che attribuirebbe quindi a Francesco Maria la carica di giudice. Infatti grazie all’investitura, avvenuta a quindici anni, il giovane Della Rovere diventava un importante punto di riferimento per gli interessi del Papa e, contemporaneamente, ne assicurava la discendenza al ducato di Urbino, fondamentale per la logistica del pontefice, alla sua famiglia, e questo spiegherebbe anche la giovane età del personaggio ritratto.

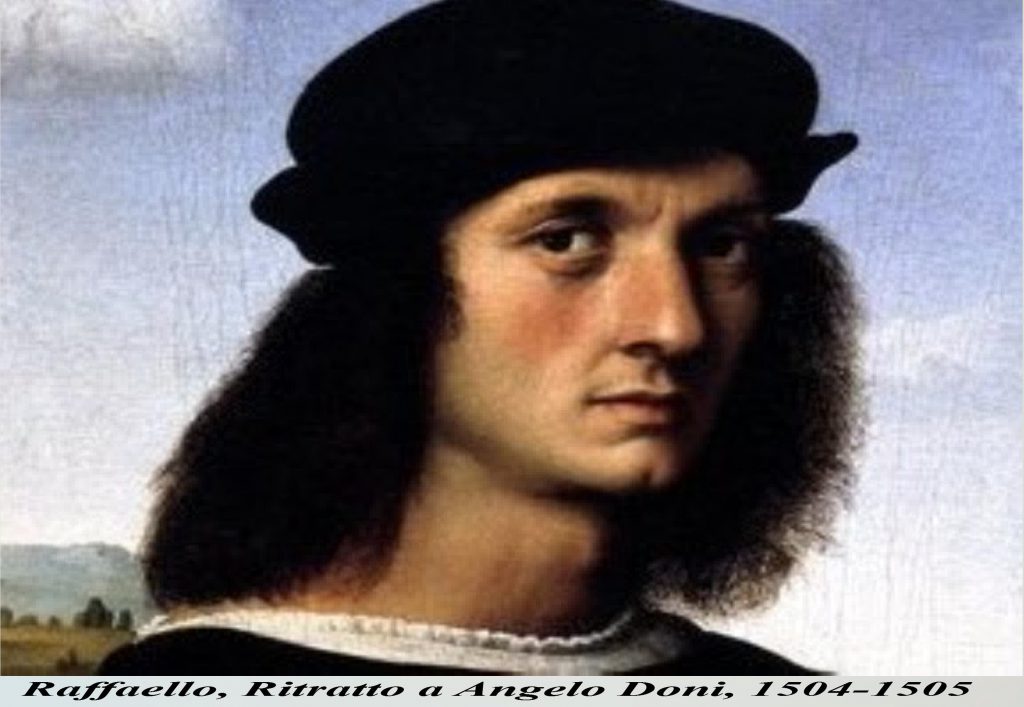

Pur dimostrando certa sicurezza, soprattutto nell’impostazione della figura, il ritratto non ha ancora la grandiosità che sarà dei ritratti Doni, e sembra ancora legato alla cultura urbinate. L’immagine è pensata, infatti, alla fiamminga caratteristica dei dittici raffiguranti da un lato la Madonna con il Bambino e, dall’altro, il committente rivolto verso la Vergine, in adorazione, con le mani congiunte in uno degli angoli inferiori del dipinto (De Vecchi ). Anche lo sfondo, con un panorama che però non riesce ancora a integrarsi con la figura in primo piano e sembra piuttosto ancora concepito come un fondo, può far pensare a un periodo ancora precedente all’esperienza fiorentina e legato di più alla cultura urbinate.

Il Bembo inviò nel 1516 al cardinale Bernardo Dovizi da Bibbena una missiva nella quale per esaltare il ritratto di Raffaello al Tebaldeo, lo paragonava a altre due opere del pittore affermando che quello di M. Baldassar Castiglione, o quello della buona et da me sempre onorata memoria del S. Duca nostro, a cui doni Dio beatitudine, parebbono di mano d’uno de’ garzoni di Raphaello (Gozio). Chi sia questo duca non è specificato, ma è vero che entrambi i personaggi erano stati assieme alla corte urbinate e, soprattutto, molto legati a Guidobaldo. È probabile che il Bembo si riferisse al ritratto di Guidobaldo oggi conservato agli Uffizi e di provenienza urbinate (Baldi) e non ritenuto del pittore urbinate da tutta la critica. C’è però un’altra testimonianza in suo favore, e cioè quanto scrive Bernardino Baldi a proposito del catafalco funebre del duca di Urbino. Descrivendone l’abbigliamento il Baldi dice che era vestito di un giubbone di damasco negro con un berrettone in capo, com’era costume di quei tempi, simile a quello col quale d’eccellente mano egli si vede ritratto, e questo abbigliamento corrisponde a quello del ritratto in questione.

7

Il duca è rappresentato frontalmente con in testa una berretta nera, il viso serio, lo sguardo fisso sullo spettatore e l’ovale lambito da due bande di capelli che scendono su ogni lato. Il vestito è certamente un abito cerimoniale, che conferisce dignità e sottolinea il tono aristocratico del personaggio, senza però eccessi, anzi con estrema semplicità (Baldi). La figura è rappresentata in un interno, ma sul lato destro si apre una finestra che dà su di una campagna, dove si intravedono un casolare con alcuni covoni, mentre più lontano una città fortificata da cui spiccano una cupola e un campanile.

Vi è in questo quadro un colore caldo e una luce calma che, effettivamente, fanno ricordare, assieme a una costruzione maggiore della figura e in particolare del busto, rispetto al ritratto di Elisabetta, il Raffaello del primo periodo fiorentino, ormai aperto a nuove esperienze. Questo porterebbe a una datazione tra il 1504-1506, che sarebbe confermata da altri elementi come l’ambientazione in un interno e l’apertura della finestra sul paesaggio campestre presente in altre opere di quel periodo, il ritratto a Maddalena Doni per esempio, o la cupola e il campanile sullo sfondo, che sono molto simili a quelli della Madonna del cardellino.

Il Vasari ci informa che nel 1506 Raffaello fu costretto a lasciare Firenze per tornare in Urbino, (…) per aver là, essendo la madre e Giovanni suo padre morti, tutte le sue cose in abbandono. Non credo che il Vasari volesse dire che proprio in quell’anno i genitori erano morti, in quanto commetterebbe un errore troppo grande. Infatti i genitori erano morti tutti e due molto prima e, a quanto ci risulta, i parenti stretti di casa Santi e di casa Ciarla erano tutti vivi. Non abbiamo in verità nessuna testimonianza della data di morte di Elisabetta, la sorella di Raffaello, e della seconda madre, Bernardina. I documenti tacciono su di loro a partire dal 1500. La cosa non potrebbe dire granché, visto che i documenti sulle donne sono piuttosto avari di notizie in quel periodo, ma forse è bene ricordare che nel 1506 Urbino fu devastata dalla peste (Pungileoni). Nulla vieta di pensare che Raffaello sia rientrato in patria a causa di un lutto provocato dalla malattia e che, una volta arrivato, si sia trovato di fronte uno scenario non certo edificante. Potrebbe essere questo il motivo di quell’espressione malinconica che si legge nell’Autoritratto degli Uffizi, nel quale alcuni, con una certa immaginazione, hanno addirittura visto la predestinazione a una morte precoce (Quatremère de Quincy ).

8

È l’immagine di Raffaello più conosciuta e che ha trovato, nel corso dei secoli, numerosi imitatori. Il pittore vi è ritratto a tre quarti, su un fondo grigio-verde e illuminato dalla sinistra, luce che proietta un’ombra sul lato destro. Sulla testa una berretta e dal colletto della veste scura esce il bordo di una camicia. Negli ultimi anni è stato avanzato qualche dubbio sull’autografia di questo dipinto, soprattutto per la sua mancanza di impianto, rispetto a altri ritratti coevi. È vero che l’autoritratto non può reggere il confronto ad esempio con quello di Agnolo Doni, ma altrettanto vero che le pessime condizioni in cui si trova e interventi di altre mani, rendono difficile una esatta lettura.

Un altro ritratto che si può attribuire alle opere che Raffaello fece per Urbino è la così detta Muta della Galleria Nazionale delle Marche ad Urbino.

9

La figura enigmatica di questa donna, che sembra avvertire un leggero trasalimento interiore, grazie a un gioco più variato e sottile di luci e ombre (De Vecchi), vestita di un abito comunque aristocratico, è stata e è al centro di discussioni. Il quadro rientra sicuramente nel periodo maturo fiorentino, come testimoniano le influenze di Leonardo, riscontrabili nell’incarno e nella dolcezza del volto, come nella posa della donna che ricorda la Gioconda o un ritratto perduto di Leonardo che Raffaello aveva studiato, come testimonia un disegno ora al Louvre (Longhi ). Vi è uno stile maturo in cui l’esempio del Perugino sembra del tutto superato, grazie all’attenzione che Raffaello dedica alla figura umana intesa anche, e soprattutto, dal punto di vista psicologico. Il carattere dell’immagine dipende dalla monumentalità con cui il pittore realizza questa figura, per cui si potrebbe avanzare l’ipotesi di due momenti di realizzazione, uno nel 1508 circa, e uno precedente di pochi anni.

Sotto l’immagine, infatti, è stato trovato un primo ritratto, che rappresenta una donna molto più giovane, la cui realizzazione è differente da quella vedibile, ma dove si può riscontrare la mano di Raffaello. La prima stesura rappresenta una donna con un abito scollato tenuto da lacci sulle spalle. L’abbigliamento della Muta, così come lo vediamo oggi, è differente, è più accollato, e anche i capelli da sciolti divengono composti e raccolti. Probabilmente fu lo stesso Raffaello a modificare il dipinto invecchiando la donna e cambiandone l’abbigliamento per il sopraggiungere della vedovanza, il colore verde era infatti simbolo di lutto. Questa scoperta ha rinnovato la discussione intorno all’identità della persona ritratta. Innanzi tutto vengono scartate vecchie proposte che non reggono più, soprattutto per questioni di datazione (Sesti). Viene meno in questo modo anche l’ipotesi del Filippini e del Sangiorgi che vi vedevano Elisabetta Gonzaga, ma potrebbe essere invece, Giovanna Feltria della Rovere, poiché la prima stesura sembra essere antecedente al 1501, anno in cui morì il marito di Giovanna, Giovanni della Rovere.

Credo che la frequenza di questi ritratti di Raffaello, e sono solo quelli che ci sono giunti, testimoni come il pittore sia stato sempre in contatto con la corte di Urbino e con la città e come, proprio quella corte, si sia resa conto con largo anticipo sul resto della cultura centro-italiana del valore di quel giovane artista. Più in generale però, la presenza di molte opere dell’urbinate nella propria città natale deve avere per forza, e non solamente dopo gli anni ’20 del secolo, lasciato le tracce su altri pittori che nella città ducale lavoravano, tanto quelle immagini erano e sono ricche di suggestioni non certamente trascurabili.

RAPHAEL URBINAS: HYPOTHESIS ON URBIN PORTRAITS.

Giovanni Santi was to be well appreciated at the Urbino court and throughout the Montefeltro area and not only for his blades, but also for his portrait activity. A genre that had evidently allowed his name to cross the borders of the Duchy of Urbino, given that in 1493 he was invited by Isabella d’Este to Mantua to perform some portraits. Unfortunately, his works of this kind have not reached us, but I believe that the son, already initiated into art by his father, could not have done without trying, even at a young age, in portraiture. In fact, there are two portraits drawn between 16-17 years by Raphael (Knab 1983), and commonly considered self-portraits. These are two drawings, one preserved in the British Museum in London drawn in chalk and the other preserved in the Ashmoleon Museum in Oxford in gray plaster with white lead, which portray a young man who remembers very closely the physiognomy of the other self-portraits of Raphael , first of all that of the Uffizi, with the due passage of time and its aging and both marked by an almost identical writing of a hand between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries which reads: Portrait of himself when young.

No wonder that Raphael practiced with his own image, as it was a fairly common practice for a young painter and think for example of Durer, to whom the two drawings were sometimes approached (Knab) .

Immages 1-2

The London drawing highlights a direct gaze fixed in the mirror, but there is no shortage of that typical wonder of a boy of that age, even if it is covered by a veil of sadness or rather melancholy which, without wanting to do psychology, perhaps reflects the the mood of a young man who had not really been lucky in that first period of life, marked by family mourning, by historical and political events that had upset the country, and by a relationship with relatives, especially those with the parents of the second mother, certainly not edifying. It is however a very realistic portrait, which seems almost the first or one of the first studies for a series of self-portraits. In Oxford there is a more evident idealization and for this reason we have seen a relationship with the portraits of Leonardo and Lorenzo di Credi (Beccherucci, 1968). Personally, even for a matter of dates, I find myself more in agreement with those scholars who see an influence of Perugino and Pinturicchio, without forgetting, indeed I think it is very important, the memory of Raphael of the Urbinate culture. Certainly Raffaello had not forgotten the portraits of Melozzo da Forlì, the sculpture of Luca della Robbia and, above all, not only the portraits of his father who unfortunately did not reach us, but the faces painted by this, faces that are treated like portraits ( Zampetti).

Serlio in one of his treatises states that Elisabetta Gonzaga, the Duchess of Urbino, was one of Raphael’s protectors, and this leads us to deduce that the young painter was in relationship with the whole court, above all for the fact that the cultural activity of this was in the hands of the Duchess. It therefore seems unlikely that the court did not ask the painter to paint portraits for the most prominent characters. It is true that the Montefeltro family had to flee before the invasion and betrayal of Valentino, but after their return in 1503, Raphael could have done some portraits. Indeed some testimonies of the existence of these portraits exist, for example in 1606 Antonio Beffa Negrini tells us that there was a portrait of a beautiful and princely lady, by the hand of Raffaello Sanzio, who would have belonged to Castiglione. Of course it is impossible to verify whether the seventeenth-century writer referred to the portrait of the Duchess of Urbino attributed to Raphael and today to the Uffizi, but nothing prevents us from thinking about it.

Not everyone agrees in the attribution of the portrait of Elisabetta Gonzaga to the painter from Urbino and many alternative proposals have been made, without however reaching conclusive proofs. Lately the attribution to Raphael has become stronger since the Urbino provenance of the painting was ascertained (Sangiorgi).

Immage 3

Raphael probably painted this portrait between 1503 and October 1504, before he left for Florence. It is possible, but it is only a hypothesis, that the portrait was made before Guidobaldo’s ceremony of adoption of Francesco della Rovere, which took place in Urbino with a big party and the participation of illustrious characters. If Raphael was in Urbino, as everything suggests, I think he also somehow participated in the ceremonies. Then the portrait of Elisabetta could be the first in a series to celebrate the event, which had to include all the most prominent personalities of the court, portraits that were not executed (or perhaps yes) for the departure for Florence.

It is a front portrait, even if the Duchess has her head turned slightly to the left, a movement that perfectly renders the character’s aristocratic character. He wears a still fifteenth-century dress, on the neck of which runs an unidentified inscription, probably the soul of a motto of hermetic origin, since at the court of Urbino hermetic research was in vogue, also for the renewed neo-Platonic climate that reigned there . It also seems that Elisabetta herself was a culture breeder (Castelli). It will not be easy to decipher this inscription in hermetic and esoteric kufic or symbolic characters, although perhaps it would not be in the wrong future to consult to this end the Corpus Hermeticum, which had already been partially translated by Ficino since 1471 with the title Poimandrhz.

The hairstyle is also from the fifteenth century, with the hair falling down the face and a parting that divides them. They are surrounded by a line with a small and very refined jewel in the middle, representing a scorpion that encloses a precious stone in the pincers. There has been much discussion about this symbol, which for some would represent the body of the motto that has already been mentioned (Baldi). In truth, even to solve this enigma, the situation should be thoroughly studied, since scorpion, since ancient times, has numerous symbolic meanings, some of which contrasting or having an exquisitely esoteric flavor (Ceccarelli). It had to be, however, a symbol very dear to the Duchess, so much so that Castiglione also talks about it in the Cortegiano, when the conversation of the participants shifts precisely on the meaning of the jewel, without however providing a solution.

Behind the Duchess opens a panorama with meadows and hills behind which the dawn seems to come. It is painted with a particularity reminiscent of Flemish painting, as indeed the fine brushstrokes from which it is composed.

One of the reasons that made us doubt about the attribution to Raphael of this portrait and that of Emilia Pio of Montefeltro, is their somewhat archaic frontal approach, which would contrast with the works of the Florentine period. However, if the dating is right, the Florentine experience was still to come, besides the fact that some critics move the date of the work a few years in advance (Oberhumber). It could also be that Raphael, at any time he painted the portrait, remembered another painting, most likely present at the ducal court at that time, the blessing Christ attributed today to Bramantino (Ciardi Duprè Dal Poggetto). The hypothesis may seem risky, but it seems to me that there are some affinities between the two paintings. It is not so much the frontal setting that gave rise to this idea, a common setting in the fifteenth century, just think of Mantegna or Antonello da Messina, as certain characteristics proper to the figure. The expression, for example, both absorbed, but almost distant with a penetrating gaze, the cut of the eyes practically identical, like, on the other hand, the nose. I repeat, it is only a hypothesis that should however be taken into consideration.

Immage 4

Even the portrait of Emilia Pio from Montefeltro, of which there are testimonies about the provenance of Urbino (Sangiorgi), could be from the same period and fall within those made to celebrate the adoption of Francesco Maria. This time the setting is completely frontal, there is no movement of the face. The gaze, noble and steady, is fixed on the viewer, the oval of the face enclosed by two bands of hair that fall on the shoulders. Unlike Elizabeth’s, the background is dark and tends to bring out the image.

Immage 5

The young man with the pommel, a portrait of sure provenance from Urbino as evidenced by the inventories and who ended up in Florence with the legacy of Vittoria in 1631 at Palazzo Pitti until 1928 and then moved on to the Uffizi. It would portray Francesco Maria della Rovere and should have been painted on the occasion of his adoption by Guidobaldo in mid-September 1504.

Immege 6

The character, a young teenager, richly wears red clothes decorated with a fur coat and has on his head a cap with always raised red flaps. It is represented by three quarters, with the bust towards the left and the eyes on the right. The hands rest on a surface and the left is stretched out on the palm, while the right squeezes a golden knob, the meaning of which is not fully revealed. However, I am inclined to accept the hypothesis, already advanced by others, that the apple would be that of Paris, which would then attribute the position of judge to Francesco Maria. In fact, thanks to the investiture, which took place at fifteen, the young Della Rovere became an important point of reference for the interests of the Pope and, at the same time, ensured his descent to the duchy of Urbino, fundamental for the logistics of the pontiff, his family, and this would also explain the young age of the portrayed character.

While demonstrating certain security, especially in the setting of the figure, the portrait does not yet have the grandeur that will be of the Doni portraits, and still seems linked to the Urbino culture. The image is thought, in fact, of the Flemish characteristic of the diptychs depicting on one side the Madonna and Child and, on the other, the client facing the Virgin, in adoration, with her hands joined in one of the lower corners of the painting ( De Vecchi). Even the background, with a panorama that still cannot integrate with the figure in the foreground and seems rather still conceived as a background, can suggest a period that was even earlier than the Florentine experience and linked more to the Urbino culture.

In 1516 Bembo sent Cardinal Bernardo Dovizi da Bibbena a letter in which to enhance the portrait of Raffaello al Tebaldeo, he compared it to two other works by the painter stating that that of M. Baldassar Castiglione, or that of the good and always honored by me. memory of our S. Duke, to whom you give God bliss, they seemed by the hand of one of the gentlemen of Raphaello (Gozio). Who is this duke is not specified, but it is true that both characters had been together with the court of Urbino and, above all, very close to Guidobaldo. It is probable that Bembo was referring to the portrait of Guidobaldo now preserved in the Uffizi and of Urbino origin (Baldi) and not considered by the painter to be Urbino by all critics. However, there is another testimony in his favor, namely what Bernardino Baldi writes about the funeral catafalque of the Duke of Urbino. Describing his clothing, Baldi says that he was dressed in a black damask jacket with a cap on his head, as was the costume of those times, similar to the one with which he is seen in an excellent hand, and this clothing corresponds to that of the portrait in question.

Immage 7

The duke is represented frontally with a black cap on his head, his face serious, his gaze fixed on the viewer and the oval lapped by two bands of hair that descend on each side. The dress is certainly a ceremonial dress, which confers dignity and underlines the aristocratic tone of the character, without excesses, indeed with extreme simplicity (Baldi). The figure is represented in an interior, but on the right side a window opens onto a countryside, where you can see a cottage with some sheaves, while further a fortified city from which a dome and a bell tower stand out.

In this painting there is a warm color and a calm light which, indeed, make us remember, together with a greater construction of the figure and in particular of the bust, compared to the portrait of Elizabeth, the Raphael of the early Florentine period, now open to new experiences . This would lead to a dating between 1504-1506, which would be confirmed by other elements such as the setting in an interior and the opening of the window on the rural landscape present in other works of that period, the portrait of Maddalena Doni for example, or the dome and the bell tower in the background, which are very similar to those of the Madonna del goldfinch.

Vasari informs us that in 1506 Raphael was forced to leave Florence to return to Urbino, (…) to have all his belongings abandoned, being his mother and Giovanni his father dead. I don’t think Vasari meant that the parents had died in that year, as he would have made a too big mistake. In fact, the parents had both died much earlier and, as far as we know, the close relatives of the Santi house and the Ciarla house were all alive. In truth, we have no record of the date of death of Elizabeth, Raphael’s sister, and of the second mother, Bernardina. The documents have been silent on them since 1500. The thing could not say much, given that the documents on women are rather stingy with news at the time, but perhaps it is good to remember that in 1506 Urbino was devastated by the plague (Pungileoni). Nothing prevents us from thinking that Raffaello returned to his homeland due to a mourning caused by his illness and that, once he arrived, he found himself faced with a scenario that was certainly not edifying. This could be the reason for that melancholy expression that can be read in the Uffizi Self-Portrait, in which some, with some imagination, even saw the predestination for an early death (Quatremère de Quincy).

Immage 8

It is the best known image of Raphael and which has found numerous imitators over the centuries. The painter is portrayed in three quarters, on a gray-green background and illuminated by the left, a light that casts a shadow on the right side. A cap on the head and the edge of a shirt comes out of the collar of the dark robe. In recent years, some doubts have been raised about the autography of this painting, especially for its lack of layout, compared to other contemporary portraits. It is true that the self-portrait cannot stand comparison, for example, with that of Agnolo Doni, but equally true that the bad conditions in which it is found and the interventions of other hands make an exact reading difficult.

Another portrait that can be attributed to the works that Raphael made for Urbino is the so-called Muta of the National Gallery of the Marche in Urbino.

Immage 9

The enigmatic figure of this woman, who seems to feel a slight internal start, thanks to a more varied and subtle play of lights and shadows (De Vecchi), dressed in an aristocratic dress, however, has been and is at the center of discussions. The painting is certainly part of the mature Florentine period, as evidenced by Leonardo’s influences, found in the incarnation and sweetness of the face, as in the pose of the woman reminiscent of the Mona Lisa or a lost portrait of Leonardo that Raphael had studied, as evidenced by a drawing now at the Louvre (Longhi). There is a mature style in which the example of Perugino seems completely outdated, thanks to the attention that Raphael dedicates to the human figure also intended, and above all, from a psychological point of view. The character of the image depends on the monumentality with which the painter creates this figure, so the hypothesis of two moments of realization could be advanced, one in about 1508, and a previous one of a few years.

Under the image, in fact, a first portrait was found, representing a much younger woman, whose realization is different from the visible one, but where Raphael’s hand can be found. The first draft represents a woman with a low-cut dress held by laces on the shoulders. The clothing of the wetsuit, as we see it today, is different, it is more popular, and even when loose hair becomes composed and gathered. It was probably Raphael himself who modified the painting by aging the woman and changing her clothing for the arrival of widowhood, the green color was in fact a symbol of mourning. This discovery renewed the discussion around the identity of the person portrayed. First of all, old proposals that no longer hold up are rejected, especially for dating (Sesti). The hypothesis of Filippini and Sangiorgi who saw Elisabetta Gonzaga also fails in this way, but it could instead be Giovanna Feltria della Rovere, since the first draft seems to be prior to 1501, the year in which Giovanna’s husband Giovanni died della Rovere.

I believe that the frequency of these portraits of Raphael, and they are only those who have come to us, witnesses how the painter has always been in contact with the court of Urbino and with the city and how, precisely that court, he realized with wide advance on the rest of Central Italian culture of the value of that young artist. More generally, however, the presence of many works from the Urbino area in one’s hometown must necessarily, and not only after the 1920s, have left traces on other painters who worked in the ducal city, both those images were and they are full of suggestions which are certainly not negligible.

È mia personale opinione che Raffaello fosse attratto dalle fattezze femminili e sopratutto dai loro volti. Molte opere lo manifestano. La Fornarina per esempio è già una piccola prova (addirittura il bracciale), nulla esclude quindi che volti femminili anche visualizzati di sfuggita potessero ispirarlo.