P.Manzoni, Merda d’artista, 1961.

Si può dire della Merda d’Artista di Piero Manzoni è bella? Credo proprio di no, e come per quella per molte altre opere d’arte e non solo moderne e contemporanee. Si può arrivare a dire “sono belle”, ma non c’è l’impatto emotivo necessario per dichiararle belle a un primo sguardo. Non mi interessano ora tutte le teorie estetiche da Platone a Aristotele, a Hegel fino a Dorfles, Ferraris o Danto. Sotto il “giudizio” di “bello” per simili opere, compreso Duchamp, c’è una mediazione, un ragionamento, una razionalità.

La “scatoletta” non è altro che una “scatoletta” che si eleva a opera d’arte e acquista una sua bellezza solo dopo che ne è stato svelato o attribuito un significato, l’importanza innovativa ecc…, ma di primo acchito non genera un senso di bellezza nello spettatore. E non si può dire che ciò sia una caratteristica di quel “genere” d’arte contemporanea (concettuale, poverista, minimalista, posthuman ecc…) sviluppatosi dopo, diciamo, la Pop Art, perché, ad esempio, davanti a un’opera come Senza titolo 1972 di Calzolari mi è venuto da dire subito bella.

P.P. Calzolari, Senza titolo, 1972

E pure se ci si rivolge a opere astratte, per cui, per esempio, mi colpisce la bellezza di un quadro di Mondrian, mentre davanti a uno di Klee ho bisogno di ragionare, sembra una stranezza, visto il carattere delle opere, ma è così.

P. Klee, Ancien Harmony, 1925. P. Mondrian, Tableau II, 1021-25

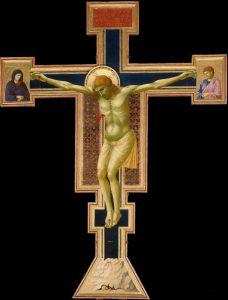

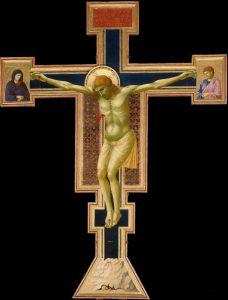

Ma ciò non è vero solamente per l’arte contemporanea. Se di fronte a una tela di Picasso del periodo cubista sintetico o analitico, non esclamo bello d’istinto, ma devo ragionarci, ciò accade anche per un dipinto bizantino, o anche gotico, con le dovute eccezioni, come i Crocifissi di Cimabue o Giotto, ma non quelli di Coppo Marcovaldo, e, a dire il vero, neppure il Ciclo di Assisi o quello della Cappella Scrovegni mi entusiasmano se non nel loro insieme, le storie narrate prese singolarmente, le loro figure, le loro architetture i loro ambienti naturali, pur comprendendone la portata e la novità rivoluzionaria nell’ambito della pittura e del pensiero medievale, non suscitano in me un sentimento immediato di bellezza.

P.Picasso,Ma Jolie,1911-12. Giotto, Cristo S. M. Novella, 1290-95 Coppo di Marcovaldo, Crocifisso di S. Giminiano, 1264 c.

La bellezza è in gran parte soggettiva, al di là della simmetria, dell’ordine, dell’equilibrio della pulcritudo ecc…, anche se dei “canoni” fissi forse, in fin dei conti, esistono. Cosa sia la bellezza è indicibile; è, e basta, scaturisce improvvisa e violenta, nel senso che coinvolge o sconvolge l’intero essere, e non solo quella attribuibile all’opera d’arte. Anche se un domani più prossimo di quello che si può presumere le neuroscienze spiegassero il suo comparire, del sentimento della bellezza, con qualche reazione biochimica nel cervello o a causa di un qualsiasi gene, non potranno mai dire perché avviene, da cosa nasce, che ruolo ha, e perché in ognuno è diversa e particolare.

La bellezza scaturisce da un qualcosa in più che va e che esiste oltre l’oggetto o il suono percepito. È sì, sensoriale, corporea, ma supera il sensibile stesso aprendo un varco a un altro mondo, forse facendo accedere al simbolico, fornendo al simbolico un linguaggio che non conosciamo o abbiamo perduto. M’illumino d’immenso, non vuol dire nulla razionalmente, perché non ha nessun riferimento sensibile: non posso illuminarmi, tanto meno di luce propria, e quanto meno d’immenso che neppure posso definire, ma, al limite, solo immaginare. Ma quelle parole aprono un altro livello di conoscenza che oltrepassa il sensibile e il matematico e genera bellezza anche attraverso lo spaesamento.

La bellezza è in sé, ma non nel senso kantiano, poiché in qualche modo ne possiamo percepire il significato, anche se non sappiamo quale sia, e ne subiamo gli effetti, anche sensibili come spaesamento psichico, brividi, aumento della temperatura, del battito cardiaco, affanno, là dove essa è intensa. E questo è un altro punto a favore della non decifrabilità della bellezza da un’ottica unicamente fisica, perché da un punto di vista biologico sono gli stessi sintomi, effetti materiali che si possono notare in un corpo davanti al repellente, all’osceno, al terrificante.

La domanda dovrebbe essere non “Cos’è la bellezza?”, ma “Da dove viene la Bellezza?”, “Perché c’è la bellezza?”. In questo senso il sentimento o meglio la sensazione della bellezza esce dall’apparato iscrivendosi, in un modo o nell’altro, nell’ordine della casualità e uscendo o precedendo quella della causalità e dalla prevedibilità.

Non si può progettare una sensazione di bellezza improvvisa, proprio come non si può progettare un amore, un innamoramento. Ti piombano addosso, e guarda a caso in entrambi, bellezza e amore, pur essendo individuali, hanno bisogno di condivisione per esprimersi.

THE BOX OF SHIT AND MORE.

Is the Merda d’Artista by Piero Manzoni beautiful? I do not think so, and as for many other works of art and not only modern and contemporary. You may get to say “they are beautiful”, but there is no emotional impact necessary to declare them beautiful at first glance. I’m not interested in all the aesthetic theories from Plato to Aristotle, Hegel to Dorfles, Ferraris or Danto. Under the “judgment” of “beautiful” for such works, including Duchamp, there is a mediation, a reasoning, a rationality.

The “can” is nothing more than a “can” that rises to the work of art and acquires its beauty only after it has been revealed or attributed a meaning, innovative importance etc… but at first glance it does not generate a sense of beauty in the spectator.

And it cannot be said that this is a characteristic of that “genre” of contemporary art (conceptual, poverist, minimalist, posthuman etc…) developed after, say, Pop Art, because, for example, in front of a work like Untitled 1972 by Pier Paolo Calzolari came to me to say immediately beautiful.

P.P. Calzolari, Senza titolo, 1972

And even if you turn to abstract works, so, for example, I am struck by the beauty of a Mondrian painting, while in front of one of Klee I need to reason, it seems strange, given the character of the works, but it is so.

P. Klee, Ancien Harmony, 1925. P. Mondrian, Tableau II, 1021-25

But this is not true only for contemporary art. If in front of a painting by Picasso of the synthetic or analytical cubist period, we do not exclaim beautiful of instinct, but I have to reason with it, this happens also for a Byzantine painting, or even Gothic, with the due exceptions, as the crucifixes of cimabue or Giotto, but not those of marcovaldo cup, and, to tell the truth, not even the cycle of Assisi or that of the Chapel scrovegni thrill me if not in their entirety, the stories narrated singularly, their figures, their architectures their natural environments, while understanding the significance and revolutionary novelty of painting and medieval thought, they do not arouse in me an immediate feeling of beauty.

P.Picasso,Ma Jolie,1911-12. Giotto, Cristo S. M. Novella, 1290-95 Coppo di Marcovaldo, Crocifisso di S. Giminiano, 1264 c.

Beauty is largely subjective, beyond symmetry, order, pulchritude, balance etc… even if fixed “fees” may, at the end of the day, exist. What beauty is is unspeakable; it is, and that is, it springs suddenly and violently, in the sense that it involves or upsets the whole being, and not only that attributable to the work of art. Even if tomorrow, nearer than one can presume, neuroscience explains his appearance, of the feeling of beauty, with some biochemical reaction in the brain or because of any gene, they can never say why it happens, what it is born of, what its role, and because in each one it is different and particular.

Beauty springs from something more that goes and exists beyond the object or perceived sound. It is sensory, bodily, but it surpasses the sensitive itself by opening a passage to another world, perhaps by accessing the symbolic, providing the symbolic with a language that we do not know or have lost. M’illumino d’immenso, does not mean anything rationally, because it has no sensitive reference: I cannot illuminate myself, much less of my own light, and the least of it is immense that I cannot even define, but, at the limit, only imagine. But those words open up another level of knowledge that transcends the sensitive and the mathematician and generates beauty also through bewilderment.

Beauty is in itself, but not in the Kantian sense, for in some way we can perceive its meaning, even if we do not know what it is, and we suffer its effects, also sensitive like psychic confusion, shivers, increase in temperature, heartbeat, where it is intense. And this is another point in favour of the non decipherability of beauty from a purely physical perspective, because from a biological point of view are the same symptoms, material effects that can be seen in a body before the repellent, the obscene, the terrifying.

The question should be not “What is beauty?” but “Where does Beauty come from?” “Why is there beauty?”. In this sense the feeling or rather the sensation of beauty comes out of the apparatus entering, in one way or another, in the order of randomness and exiting or preceding that of causality and predictability.

You can’t design a sudden sensation of beauty, just like you can’t design a love, a love. They swoop down on you, and randomly in both, beauty and love, although individual, need sharing to express themselves.

Un articolo che genera Bellezza. Grazie!

È bello ampliare i propri orizzonti.